Off on a Wander II - Food

As I reflect on 6 months of travel, I know I need to write about food. For me, food and travel are inseparable experiences, much as life and food are inseparable. When I find myself in a new place, one of the first things I want to know is what and how the people eat, how it informs their culture, and how their relationship with food shapes their lives. I often find myself investigating history and tradition as it is expressed through food. I tend to wander curiously in markets and seek out foods and flavors that are new to me. We’ve been fortunate to sample a number of deep and diverse food cultures in the last six months and I’d like to share some thoughts and experiences from that.

The last three months have been great – after Nepal, we moved to Turkey to take a paragliding maneuvers course and do some backpacking along the Lycian Way, a long distance hiking route on the Aegean cost. From there we traveled to southern Germany and bike-toured along the Danube river from its source in Donaueschingen into Austria, something I’d wanted to do since my last bike tour in Germany in 2010. We visited the Alps in France for more paragliding and had a rendezvous with a friend and fellow paraglider, and then spent a month in the British Isles, first exploring Ireland’s southwest coast with family, and then enjoying a restful stay in rural Devon, England to further our pottery practice. We continued our efforts to learn the local languages while traveling, which led to deeper connections with the people – Turkish and German we made good progress at gaining functionality, French and Gaelic not as much. Without particularly intending to, we found ourselves chasing Spring weather, which turns out to suit our interests and activities quite nicely.

Photos: (1) Backpacking the Lycian Way in Turkey in April (2) Bike touring in Southern Germany in May (3) Flying over Lac du Annecy, France in June (4) Exploring SW Ireland (Alihies) in June (5) Riding bikes in Devon, England in July.

What follows is an attempt to describe six months of travel from the perspective of food. As a rule, we are vegetarian humans in the foods we prepare for ourselves, but do eat meat when it is served to us or when it is culturally obligatory. Thankfully meat isn’t a very exciting food (or necessary to make food exciting) and it turns out that most of the time it isn’t essential to experiencing the food culture of a place. Still, we have tried meat dishes on occasion when it seemed like an essential part of the food culture. Also, being that the COVID pandemic is ongoing, we have tended to shy away from restaurants unless we can eat outdoors. This means more home cooked meals, some take out, a few restaurants, and lots of picnics.

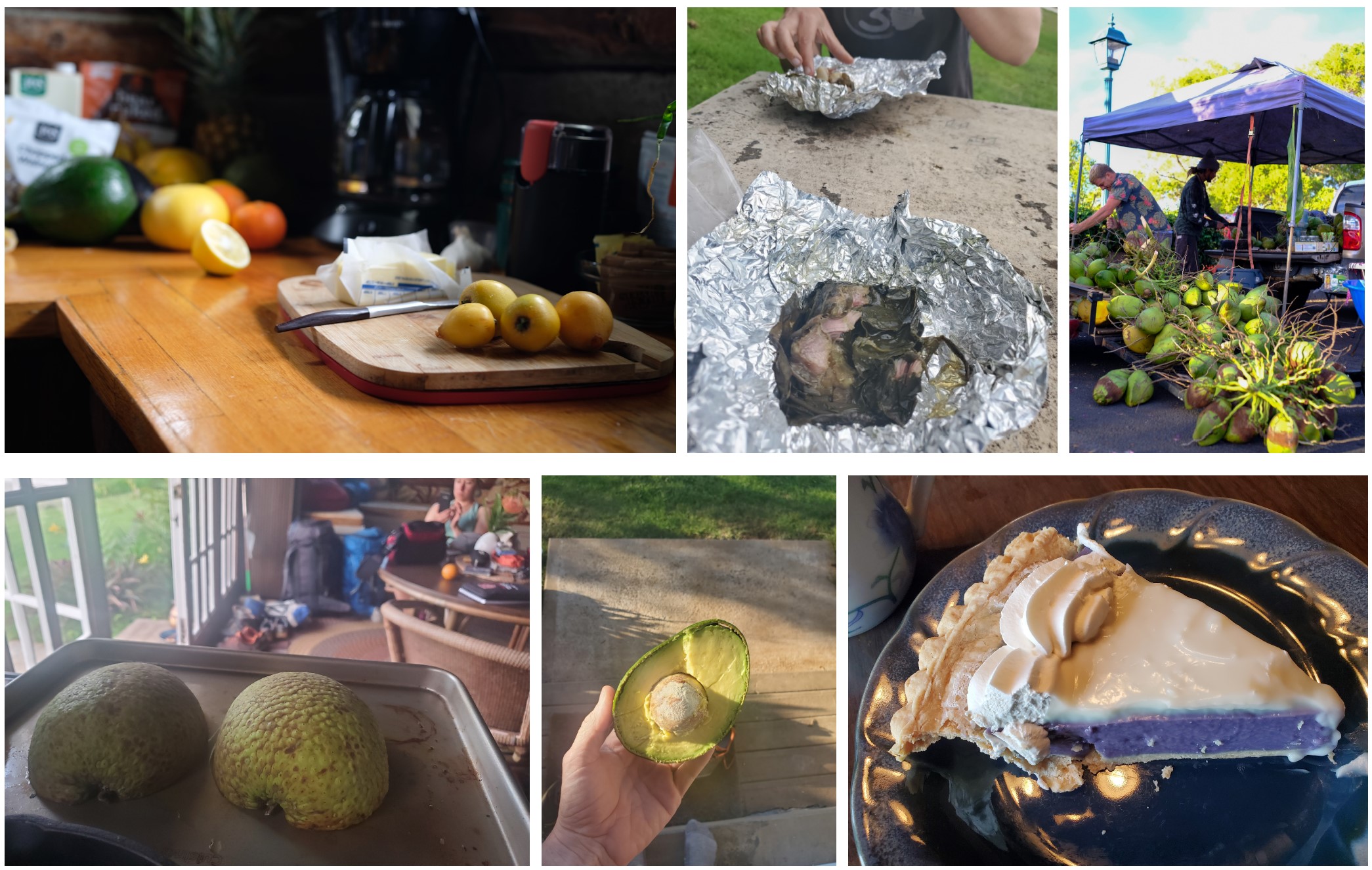

We started our travels six months ago in Hawaii, where the food culture is interwoven with a history of (often violent and arguably ongoing) colonialism. Local subsistence foods (like poi, or taro) and fish are served alongside imports that describe various colonial epochs. Sometimes dishes are effectively invasivore, such as the widespread consumption of pork, a result of hunting of the local, introduced but now widespread, wild pigs. One of the tastiest things we ate in Hawaii was Lau Lau (pork wrapped in Taro leaves and slow cooked in a steamer). Hawaii is an exceptional place for fruit and we ate plenty of it - avocados, lemons and limes, breadfruit (ulu), papaya, annona, dragonfruit, pineapple, coconut, and loquat. Near where we stayed in Kula, we also found acres of Hachiya persimmon, presumably planted by (or for) Japanese immigrants. With the sheer number of resident and feral chickens, fresh eggs are easy to find. Hawaii’s food culture is a vibrant mixture of many cultures and I’ve felt like the tourist-centric economy makes it difficult to fully parse what is authentic and what is a manufactured experience. Nevertheless we ate very well in large part by focusing on what was grown locally, stopping at roadside stands at any and all opportunities, and visiting the local farmers’ market for our weekly shopping.

Pictures: (1) Backyard loquats and various fruits (2) Lau lau from a roadside stand (3) Coconuts at the Pukalani farmers’ market (4) Breadfruit (Ulu) ready to go into the oven (5) a really good avocado (6) Taro pie - a culinary intersection.

In Spain we were introduced to Andalusian cuisine, which is perhaps more rustic and agrarian than the cuisine in the northern parts of Spain. With the COVID pandemic ongoing, we avoided restaurants but didn’t feel a great loss in doing so as many of them had menus composed primarily of meat and chips (fries) in various configurations. Instead we ate fresh foods we could find at markets and shopped at the farmers’ cooperatives (the best place to find cured meats, cheese, and olives it turns out). The cuisine in Andalucia appears largely informed by what the region grows well – tomatoes, olives, and…Iberian pigs. Food has less of a Moorish influence than one might expect given the history of the region. Spanish supermarkets don’t provide many creative options for vegetarians and one gets the impression that many meals at home center around meat and bread or potatoes. While we were in Andalucia, however, both Tagarnina (Spanish oyster thistle) and wild Asparagus came into season and it was common to find villagers in rural places foraging for both along the roadside or amidst the olive fincas. We were also treated to a number of excellent home cooked vegetarian meals at Artesania del Prado while practicing pottery there, including a fantastic (and massive) paella cooked by a family friend. Green olives are excellent and widely available and we tried many varieties including the bitter and firm alorena olives, which we gained a taste for with some practice. While in the cities of Seville, Cordoba, and Granada we sampled a variety of tapas, manzanilla (a mild, yeasty sherry), and churros with chocolate and coffee. Tapas as a food tradition is fantastic, but our best tapas were probably those we prepared ourselves since there was a lot of variety in quality among those we tried at eateries (and again there tended to be a preponderance of meat and bread - tasty but a bit repetitive).

Photos: (1) A tapas spread in our campervan with salchichon (salt pork), a mozzarella-like cheese, egg-flavored potato chips and a giant container of spicy olives (2) churros, coffee and chocolate in Ronda (3) foraged asparagus picked on a run in El Gastor (4) sherry from the cask in Malaga.

Our next stop was Nepal, the magical land of the magnificent dal bhat. For me, Nepal is a food paradise. Dal bhat, the national dish, is lentils (dahl) and rice (bhat), often served with a vegetable or curry and aachar (spicy pickle). I learned quickly to ask for my food “piro” (spicy) since the assumption is that westerners have a delicate (simple?) palette and wouldn’t want the food made with the normal amount of spice. Nepalis eat this meal twice a day and for the most part, so did we, with enthusiasm, while we were staying in Nepal. As dal bhat is a hearty meal it is best paired with hard labor (or exercise) and having a good appetite is definitely a compliment to the cook. We were also treated to some special foods, including sel roti (sweet and crunchy, ring shaped rice-based fry bread), chamre bhat (buttery sticky rice), tibetan bread (flat chewy fry bread) with sugarcane molasses (yum!), sisno (nettle stew), silam aachar (a pickle made from shiso seeds), popcorn, and chapati (Indian flatbread) with curry. Afield from dal bhat, there is certainly some noticeable influence of Tibetan, Indian and Chinese cuisine imported into daily fare (e.g., tsampa, chapati, lo mein). We drank copious tea, often sweet, including some excellent masala chia (spiced tea), sometimes with fresh buffalo (or cow) milk. Throughout our time in Nepal, we stayed in homestays and were treated as guests at the dinner table. Meat is generally reserved for special occasions (or tourists) and in Nepal and we didn’t really eat any. Without refrigeration in the vast majority of households, food is always made fresh and vegetables are generally foraged or harvested the same day which gives every dal bhat a feeling of locality and immediacy, adding to the delicious array of textures and flavors.

Photos (1) Tibetan bread with curry and sugarcane molasses in Arnakot (2) making tea in a home in Dhorpatan valley (3) a nice dal bhat spread with lots of pickles at Mardi Himal high camp (4) making sel roti and (5) making curry with Apsara in Pokhara.

Next we spent time in Turkey, particularly the historic area of the Lycian civilization along the Aegean coast. From our limited time there we noticed that Turkish food in this area has some similarities to Andalusian cuisine - olives, tomatoes and cucumbers are ubiquitous. There is a strong herding tradition and rambling goat herds are common in the nearby hill country. We tried the famous local delicacies including doner kebab (a perfect quick meal during a day of paragliding – with extra yogurt, chile and pickles, please!), manti (tiny raviolis!), mezza (similar to tapas, but perhaps better?), menemen (similar to shakshuka), gozleme (similar to, but better than, crepes), baklava (so many kinds!), turkish ice cream (with salep, a thickener derived from increasingly endangered wild orchids) and many varieties of lokum (turkish delight). There are a few things the Turks just seem to do better than everyone else and one of them is yogurt. Even the cheapest yogurt you can buy in Turkey is better than anything you can find in any other country I’ve visited (unless you’ve made it yourself). The sour and salty drinking yogurt, Aryan, is also fantastic. Tea is exceptionally good, strong, and ubiquitous in Turkey and their method of brewing it at concentration and diluting to taste is hard to beat, especially if you want to drink tea all day long (I do!). Turkish breakfast is among the best in the world with an array of vegetables, cheeses, meat, eggs and bread (especially simit – a donut shaped sesame bread). Our best meals generally came from small eateries with a daily fixed menu of “home cooking”. While backpacking we munched green almonds and mulberries on the trail, as we were shown to do, both of which are easy to find when in season. While I felt like we only scratched the surface of Turkish cuisine, we had a fantastic time and hope to go back and explore other regions as well.

Photos: (1) all manner of Baklava (2) rice, beans and stewed vegetables, served with flatbread and aryan is a typical meal (3) green almonds which taste a bit like under-ripe peaches.

Following Turkey, we had a whirlwind tour of some of our favorite places in Western Europe - southern Germany (Bavaria), Austria, and the Haute Savoie in France. These are places similarly famous for, and very proud of their food culture. In southern Germany we arrived in time for Spargelzeit (Asparagus time) and most restaurants have a tageskarte (daily ticket) with seasonal fare. The local affinity for Biergartens made finding outdoor dining options quite easy. We enjoyed green garlic spaetzle, white spargel with hollandaise, wienerschnitzel, brezeln (pretzels) of all sizes and a staggering array of desserts. Among the desserts that especially stand out were the zukertort (an Austrian specialty), rhabarberkuchen (rhubarb cake), bienenstich (bee sting cake), nusstorte (nut cake) and quark zopf (quark pastry). Becky and I decided that we would choose a German bakery over any in the world, which may be a controversial statement, but I stand by it. Being that we were primarily bike touring in Germany and Austria, following the Danube across Bavaria from the west to the east, we ate heartily and happily to recoup spent calories.

Photos: (1) Green garlic spaetzle with caramelized onions in Sigmaringen (2) Maultaschen, a kind of German ravioli in Hausen im tal (3) strawberries, quark zopf and raspberry jam from the market in Erhingen, (4) white asparagus with hollandaise, new potatoes and wienerschnitzel in Passau (5) Zukertort in Aschach an der Donau (6) Brezeln and Helles beer in Munich.

The French alps, or the Haute Savoie, is about cheese, at least for us. Few places in the world have such an exceptional selection and diversity of fresh regional cheeses of such high quality. The alps seem an ideal place to be a cow or a goat and there are quite some herds of them, enjoying the fine life munching tall grass intermingled with wildflowers. Apart from the odd bistro with a daily special, we’ve yet to fully explore restaurant cuisine and so most meals in France were picnics. In a place where baguettes and cheese are everywhere, it just seems like the right approach and it pairs well with paragliding and hiking, our primary activities in the Alps. Pastries, especially croissants, are also amazingly good and while it’s near impossible to get a full cup of coffee to go along with it, there’s no better way to start a day than with a pastry at a French patisserie.

Photos: (1) A nice wheel of washed rind goat cheese (Abondance variety, aged on spruce boards) (2) an eclair and espresso in Le Touvet (3) typical picnic spread including a nice brie, sesame baguette, fresh strawberries and hummus in Doussard (4) fueling up for launch at Montmin with an almond croissant.

We wrapped up 6 months of travel in Ireland and England. These are places that are perhaps more infamous for their food than famous, but nevertheless, we ate well. In southwestern Ireland pubs are the quintessential eateries and the basics are fried (or baked) fish and hearty stews. Irish stout is, I suppose, a food of sorts, and we had plenty of that. More than a beer, an Irish stout is a sort of cold, creamy and comforting experience. We tried the standard Irish breakfast and the white and black puddings which were tasty enough. Throughout Irish cuisine you can see tradition and hardship interwoven, wherein many staple foods were likely subsistence foods during times of scarcity, or celebration foods in times of prosperity. Despite my enthusiasm for beans, I’m not sure I like them so much with my eggs, and mushy peas may be more understandable, to me at least, if you could find a bottle of hot sauce to give them a bit of spice. Irish tea is stronger and better than most, and we drank it in impressive quantities with oaty biscuits (cookies) - especially on rainy days with a book. I did enjoy the Irish soda bread, with plenty of good butter. In the Westcountry of England we ate plenty of scones with butter or jam and clotted cream and also tried a pasty or two at the local market. English cheese is delicious and varied, perhaps only second to France, and we became regular visitors to the local cheesemonger in South Molton, sampling a wide variety of cheddars (and the Cheddar-proximal cheeses like Gloucester), blues, washed rind experiments, and delightfully bloomy cheeses. Having sampled English curry I think maybe it’s best not to. Being in the United Kingdom, I noticed how similar their food is to American food (for good and bad) and was able to see the US food more clearly as being a derivative of English cuisine.

Photos: (1) Fish and chips served with curry, tartar sauce and mushy peaks in Doolin (2) pints of Murphy’s stout on a sunny day in Alihies (3) Baked Hake with potatoes and (lots) of butter at Reenard Point (4) a full English breakfast, vegetarian version (with vegetarian sausage) in South Molton (5) sultana scones with whortleberry jam and clotted cream (6) a hot pasty at the South Molton saturday market.

Collecting some central threads, as we’ve been primarily traveling in rural areas, we noticed similarities in the cuisines even spanning cultures and continents. Rural (country) food as a concept, transcends borders. It is stylistically simple, rustic, and composed of what’s immediately available and seasonal. This country-cooking is typically comforting, filling, and calorically dense - meant to be balanced against a lifestyle of hard work. We were also inspired to see foraged foods appear in the local cuisine in many places we visited, and it stands to reason that areas with centuries spent developing a food culture would have adapted to, and celebrate what grows naturally nearby (different, certainly from food in the USA, youthful and international by comparison). These are the kinds of foods that connect people to a place and describe the relationship between the people and the land and environment in which they reside. This relationship can tell stories of survival, exploitation, or ingenuity. In some places the history of prior civilizations (and colonial campaigns) is apparent in the food, while in many places those prior cultures appear oddly missing, marginalized, or reinterpreted. In most of the places we visited there is a strong national identity around food, though the degree to which each country is successfully protecting their unique culture is perhaps variable and debatable. Especially in rural places, there is a risk of dilution and replacement of traditional foods with those that are easier and faster to prepare as relative wealth and access increases. Perhaps this is the greater good for the people who live in these places, but it is certainly a mechanism for change that is worth noticing.

As we meet the halfway mark for our trip, there is a sense of transition. The remaining time does not feel endless, but it does feel significant. Approaching that halfway mark we decided to reflect on what parts of the prior travel we most enjoyed and what we would like more of, so that we could integrate those reflections into plans for the remaining six months. In the last few months, the world, collectively, has decided the COVID pandemic is over. This has led to greater opportunity to visit places that were closed to travel just a few months ago, but also more risk (perhaps) for the traveler. We continue to feel fortunate for the opportunity to have such adventures, while also feeling resolute in our desire to live adventurous lives. Eating adventurously is certainly part of that and a continuous lens with which to experience place and culture. In the next six months we are looking forward to more time in wild places, visits with friends and family, learning and honing new skills, and plenty of flying, hiking, and biking.